The rise of the decline of everything you know and love

As you’re probably aware, recent years have seen a continued meteoric rise in technical innovation. Not only has the tech itself improved, but the infrastructure supporting it.

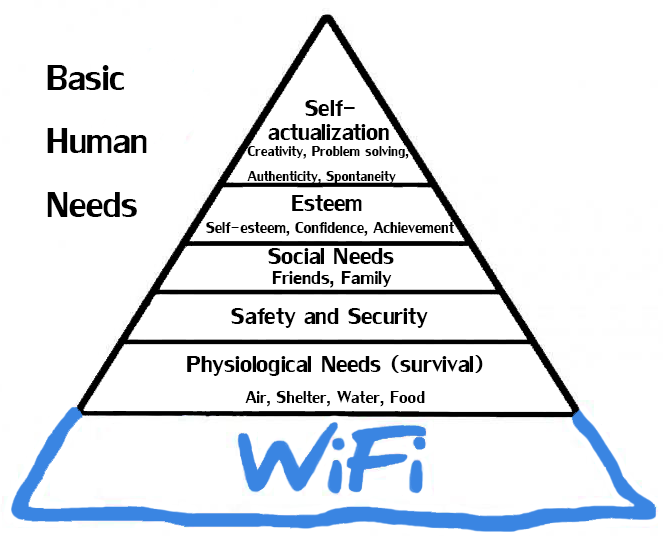

With improved data networks, the almost-universal availability of free WiFi and the endless march of smartphone after smartphone, we’ve made an almost pain-free transition to an infrastructure that enables engagement with the Internet at a pace and with a confidence that feels, arguably for the first time, natural and simple. Finally, everything works, almost.

Generally, recent apps now provide a more consistent, simple and less erroneous online experience, and far more robust functionality than those of just a few years ago. Therefore, those who previously may have been fearful to truly embrace online are now taking confident strides. Grandma has invaded your Facebook.

This diversified pool of confident users has, unsurprisingly, seen the blending of new and pre-existing cultures online – and the rise of an antipathy towards those cultures (likely due to overexposure), driven by an (largely media-managed) analytical and curious modern mindset aware that they are being marketed to.

Take, for example, the endless discussion and derision around the ‘selfie’ (a ‘trend’ that has existed since the dawn of the photograph), the increased discussion around and ‘mainstreaming’ of what would’ve been once-niche subcultures and the general democratization of popular culture – everyone is exposed to far more ‘culture’ than before.

Did previous generations widely discuss the (tedious) idea of a society at ‘Peak Beard’, or have such a detailed dialogue about a novelty café? Or even indulge this sort of thing as a concept at all?

We, as a generation, are highly aware of the context of our societal existence, and how we connect to part of a larger whole.

This ingrained meta-analysis can and does lead to cultural backlash – the true subject of this post. There’s a small but ever-growing call to return to ‘simpler times’ (if they ever really existed), or at least undo the inanity of some of our more recent creations.

The groups calling for this tend to be fairly niche and gentle in their protest – something likely spawned by a society that rewards specificity with bemusement, as opposed to distrust or ignorance.

‘Misanthropic ironic neo-luddite’ is almost a subculture of its own, prone to discourse around the fruitlessness of the modern existence. See The Onion, Daily Mash, or Facebook groups such as Get In The Sea and We Want Plates.

They are amusing, and their burgeoning popularity may point to a wider trend. Inherently cynical in nature, there’s also an undercurrent of ‘genuineness’ and nostalgia in the messages espoused by these groups. Is it worth brands moving towards this direction, or if they have the heritage and the steadfastness to not have bought too heavily into modern culture, leverage this to boost their cache? Is the time nearly upon us for those brands too slow to pick up a smartphone to seize the limelight? Obviously whilst attempting to navigate the irony of a brand attempting to pour scorn on the concept of modern advertising in an attempt to curry favour, and essentially, advertise themselves. We’re getting meta.

Certain brands have made this their prerogative ahead of time – Newcastle Brown Ale, Unicef (see below) and Go Compare have all attempted to capitalize on a culture so self-aware.

Can this be done authentically? It depends – once you’ve headed down this path, it’s tough to go back. See Budweiser’s efforts to sponsor the world of football after producing this ad – creating a rod for their own back.

It inherently appeals to a small ‘subculture’ – those gunning for mass appeal are best to stay clear, and arguably these MKNL groups do not welcome marketing as a concept…

A better approach, perhaps, is to (quietly) ask oneself ‘Is this wanky?’ when making a decision about your brands’ marketing. If it is, don’t do it.

Sounds simple, right?

Find Out More

-

Platinum CMS Award

March 13, 2024

-

Changing Communications Tack at Mobile World Congress

February 21, 2024